During quarantine, I have found that I'm spending a lot more time reading. I used to do my best leisure reading on planes or trains, on the beach or by the pool, but since none of those things are happening right now, I'm rediscovering reading as a lovely, screen-free way to spend time on the weekends.

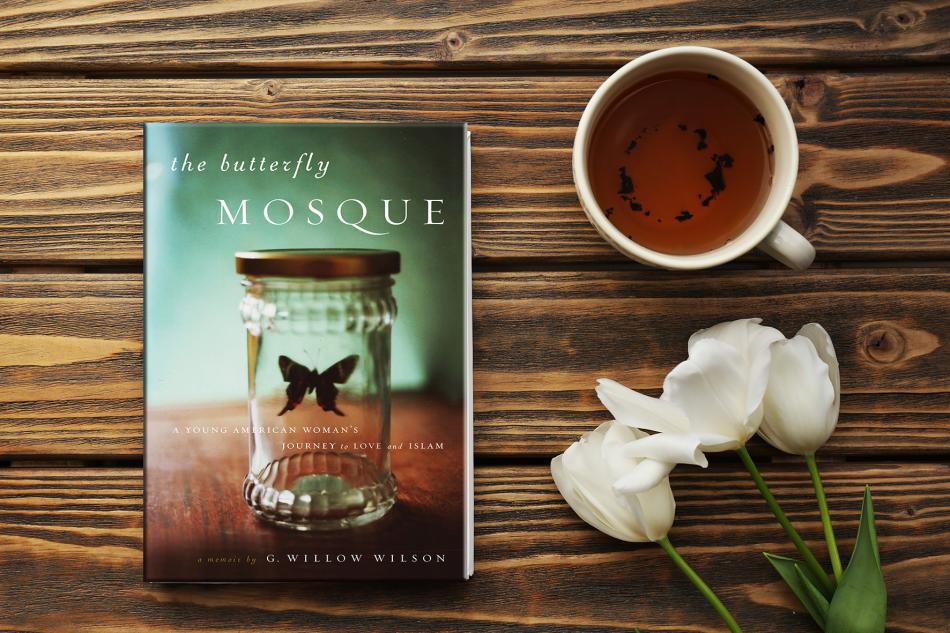

I recently finished the memoir The Butterfly Mosque by G. Willow Wilson. It's Wilson's account of moving to Cairo, Egypt after college.

During the global pandemic, where travel is not permitted, being transported to the open air markets of Cairo felt like a gift. Wilson describes her surroundings in such vivid detail. I was completely immersed.

Wilson was raised in Colorado and after graduating from Boston University, decided to move to Egypt to teach English. While still in the States, she had converted to Islam. Here she writes about how her post-college years were drastically different than most Americans her age, "Four years ago - no, two years ago - I could not have envisioned this, I thought. I could not have guessed that I would stop drinking at twenty-one, or that a dentist's office could become the scene of a clandestine romance. I had come to Islam and to Egypt without plans or expectations. I did not know who I was going to become, having made choices that steered me so dramatically off the path I was raised to walk. Everything from 9/11 to the Arab bad guys in action movies made me worry that those choices would lead to tragedy. Instead, they had led me to someone who was familiar from the moment he appeared on my doorstep, someone who cared enough to translate this confounding new reality into a language I understood."

A big chunk of the book is devoted to the love story of Wilson and her husband, Omar. He came into her orbit as a friend offering to show her around the city and ultimately became her rock.

At times, she found living in Egypt extremely difficult, but because of the immense support and kindness of Omar's family, she repressed a lot of those concerns. On page 139, she says, "Uncle Sherif, who had given me my Muslin name, had a way of looking at me with worried sympathy and silent assessment. It was as if I was a wilting flower and he was trying to decide whether I needed more sun or less, more water or more heat, to survive this foreign climate. I did not want to tell him or any of my family-by-marriage what I did need, because they could not have given it to me, and this would have made them unhappy: I needed to be able to walk in the street without being harassed, to be able to sit in a cafe by myself, I needed protein, I needed books. I did not believe that the color of my passport entitled me to these things in a country whose own people could not have them, and so I could not in good conscience move among other expatriates. I was stuck between two kinds of silence: the silence that kept me from telling the people who loved me what I needed, and the silence that kept me from seeking the sympathy of westerners."

The final third of the book explores the clash of cultures. Wilson grew up in the States, but really grew into her adult identity in Egypt. I thought she described the juxtaposition of those expectations beautifully.

On page 297, "At an age when most women were still dating, I was married, caught up in establishing a household and settling down. But because I was a woman, I was sheltered in Egypt in a way I wouldn't have been in America. I had no idea how to operate a car beyond turning the key in the ignition; I couldn't change a tire or even check fluid levels. I didn't know how insurance worked. In Egypt it would be unthinkable to ask a woman to move something heavy, or perform a mechanical task more complex than changing a lightbulb; even today I have to remind myself to attempt these things on my own before asking for help. What I can do is barter. Using herbs, I could cure a mild case of dysentery without antibiotics. I could tell if the live duck I was about to buy was overfed to make it look healthier. I could argue with a man holding a semiautomatic rifle without feeling afraid. I could write a thousand words a day while fasting. These were the things I knew. All the strengths I had developed as an adult were Egyptian strengths. Yet I was not Egyptian, and barely a day went by when I did not feel an eddy of restlessness."

I love this book. I am not sure I ever would have picked it up on my own, so I am grateful to my bestie who recommended it and loaned me her copy.

If you are looking for a story that will take you far, far away from our current reality, this is it.

*Image courtesy of Sisters Magazine.